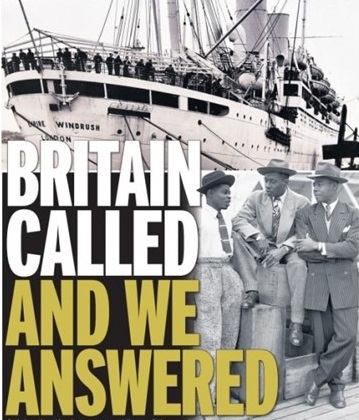

Windrush: A generation that got the nation going

Calvin Moorley, Professor in Adult Nursing and Chair for Diversity and Social Justice, shares a his thoughts about Windrush Day and his personal connection to the annual celebrationThe theme of this year’s Windrush Day celebrations is the personal meaning of Windrush – to individuals, groups, and communities.

This landmark voyage signified the beginning of Britain becoming a racially and ethnically diverse nation. The Windrush generation is a generation that cared (nurses), educated (teachers), manufactured (industry – production of steel, coal, iron, and food), and drove (transport) this nation to becoming a rich tapestry of culture, with all its practices, including food and music.

Much of this is captured by the annual Notting Hill carnival. Carnival is important as, historically, it’s the celebrations that marked the end of slavery in the Caribbean islands and the calypso music played is a parody that was used to send messages to the white slave masters – today it’s evolved into sending messages to politicians on societal issues.

My parents were part of the Windrush generation – I grew up in Trinidad and Tobago – but they never made the journey to Britain. My uncle and my father discussed boarding the Empire Windrush and my pa was too in love with my ma to leave her behind. But almost 45 years later, thanks to my uncle, I’m here and I can truly say, in the words of Lord Kitchener, London is the place for me!

The meaning of Windrush to me is that this generation made a voyage to the ‘motherland’ – most of the Caribbean islands were colonised by the British, so those that made the voyage to Britain were here to help get the mother country to get going again in a post-war period.

Oral histories have taught me this was not an easy task, and the prejudice and discrimination African Caribbean migrants encountered because of their race is well documented in books and films. When I speak of race in this context, I refer to the construct associated with the colour of one’s skin.

My generation is still dealing with the after-effects of these practices, which are no longer overt in signs such as ‘No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs’, but have become hidden and shrouded in polices, covert practices and micro-aggressions that keeps racism alive in this nation across all systems, such as education, health, justice, welfare, and employment.

Having not been born in this country, I share some Windrush experiences – for example, leaving my homeland and heading off to a better life, and I’ve also experienced racism and homophobia while living in this country. The Windrush generation is from a race that’s steeped in slavery and colonialism; and the effect of this practice is an area that my generation is committed to changing.

What does the future look like?

I’m pleased to be working at London South Bank University (LSBU) and to hold a Chair for Diversity and Social Justice. In my opinion this signals the progressiveness of the organisation to acknowledge the importance of diversity and social justice. LSBU is the largest provider of healthcare education in London and one in five of our nurses, midwives and health visitors is from a minority ethnic background, and they’re more likely than others to choose nursing as a career. This means LSBU has a very diverse healthcare student population, and my role is to ensure racial equality and the appropriate level of support to help all students achieve their best.

This involves having everyday conversations on the awarding gap for students, progression of staff from racially minoritized groups, to help the organisation to take an intersectional view when considering matters of race. I will lead the University in the Race Equality Charter submission, and to be honest, this is scary stuff! However, it’s an opportunity I’m grabbing with both hands as it’s my chance to gain that net value of zero on racism.

Also, on a personal note this contributes to the dream of those who made that Windrush journey. In this interview I did for the Mary Seacole Trust, I discuss the contribution of the Windrush and post-Windrush generation to nursing – I’m a nurse by profession and still practice in the intensive care environment – and how Caribbean nurses and midwives of the generation have been a cornerstone of the NHS.

Windrush has several meanings to me, one is that I will use ‘my Chair’ to gain a “net value of zero on racism” (a phrase I picked up from Tracie Jollof). So, this year, Windrush means gaining a net zero value on racism at LSBU and the health service.

Windrush means the struggle to be accepted, and I still see this today in our society. I see women of colour I work with in nursing, place their career progression on hold to work extra shifts so their children can get a better education, I see racially minoritized people overlooked for promotion because someone held a preconceived idea of them, or Black and Brown people over-represented negatively in some systems, and here is where stigma is contagious and can lead to unequal outcomes for ethnic minority groups. But it also means celebrating the contributions of Caribbean migrants to this country and all the great and good they have done.

I wish you a happy Windrush Day and hope you will join me in making the net value of zero on racism and embracing and celebrating the richness of racial diversity.